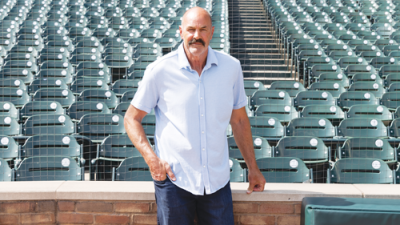

After having seizures for more than a decade, Farmington Hills resident Peter Varga said he hasn’t had one in three months following a surgical procedure.

Photo provided by Amanda Klingbail

FARMINGTON HILLS — After having seizures for more than a decade, Farmington Hills resident Peter Varga said he feels like a normal person again.

In 2005, Varga had the first of what would turn out to be many seizures after returning home from a work trip out of the country. His wife, Marisa, called 911, and emergency medical personnel showed up in his bedroom.

Although Peter Varga had “no clue” what was happening, he learned that he’d had a grand mal seizure in his sleep.

After returning home from his work trip, Varga was sick with a virus, but to this day, he has no explanation for why he had a seizure and why many more were to follow.

He is an engineer by trade and has a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering and a master’s degree in industrial operations.

After graduating from Livonia Churchill High School, he attended Schoolcraft College and Lawrence Technological University.

“I came home, got really, really sick, and that’s when all the fun started with having epilepsy, unfortunately,” Varga said. “I didn’t know what epilepsy was, and all of a sudden, 911 showed up in the bedroom. And of course, that’s what I was told, because I was completely out of it. When you have a grand mal seizure, you don’t know what’s going on; when you wake up from it, you don’t have a clue.”

He began seeing a local doctor, who was putting him on different medications and having him take different tests.

“After 10 years with that doctor, I’m like, ‘We need to figure out something different,’” he said.

Varga was at a point in his life where he was having multiple seizures a day and having one grand mal seizure around every three months.

A grand mal seizure is a more intense form of a seizure that involves a loss of consciousness and violent muscle contractions.

“It’s hard to watch. … It’s scary,” Marisa Varga stated in a press release from Corewell Health William Beaumont University Hospital. “And there’s not much you can do, other than try to stay calm, especially for the kids. I think the biggest thing is making sure that he is safe, doesn’t hit his head or hurt himself.”

In 2018, after having a seizure while driving home from picking up his then 3-year-old daughter from daycare, Peter Varga went to Corewell Health William Beaumont University Hospital, which is the new name for Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak, and met with epileptologist Dr. Andrew Zillgitt.

Zillgitt is part of the Beaumont Adult Comprehensive Epilepsy Clinic, a neurology subspecialty clinic at Beaumont University Hospital.

The clinic is in the neuroscience center and specializes in the evaluation and treatment of epilepsy and related seizure disorders.

“Dr. Zillgitt said, within the next three to four years, these are the tests and surgeries we’re going to do because your medication isn’t working anymore, and we need to find a way to get control of your seizures,” Marisa Varga stated in the release. “And everything he laid out for us has happened for Pete.”

Peter Varga was diagnosed with drug-resistant focal epilepsy, meaning multiple anti-epileptic drugs weren’t enough to control his seizures.

A decision was made for him to undergo stereoelectroencephalography, known as SEEG, in November 2020. It is a surgical procedure to identify the area of the brain where seizures originate.

The procedure involved doctors drilling 18 small holes into his skull and using a robotic arm to place electrodes internally throughout his brain.

Over the course of the 14 days following the procedure, Peter Varga had a recorded 115 seizures, including one grand mal seizure, the release states.

Of the seizures, 112 were determined to have come from the left side of his brain.

That information helped doctors understand where to implant a responsive neurostimulation device, known as RNS, that monitors for abnormal brain activity and automatically delivers electrical pulses to prevent seizures before they happen.

The device also collects data to fine-tune patient care.

In an interview, Zillgitt said that there are about 4,000 such devices in the United States.

In December 2021, a neurosurgeon removed three parts of Peter Varga’s brain on his left side — from his temporal lobe, amygdala and hippocampus.

The primary functions of the temporal lobe include memory, auditory processing, language processing, visual processing, emotion control and response, facial recognition, and speech.

During the surgery, Peter Varga was woken up and responded to questions, with the surgeon stimulating areas of his brain that he wanted to identify to protect his speech and language functions.

“Granted, it has taken a year because of the fine-tuning, so-to-speak, and having the left side of my brain removed — good portion of it — and the doctors making adjustments, and also a little bit of medication adjustments; I am now in the phase of, ‘OK, let’s start taking you off of medication,’ because I feel much, much better,” Peter Varga said. “I feel back to, quote, ‘normal.’ I’m not feeling fuzzy. … I haven’t had a seizure in three months.”

Marisa Varga said she has noticed the difference.

“He’s coaching soccer and coming to our kids’ events again,” she stated in the release. “Friends and family have noticed that he’s able to hold conversations. He’s just overall feeling better. … We were on the verge of losing hope.”

Peter Varga stopped driving after having a seizure while his daughter was in the vehicle. However, he said he is looking to get his driver’s license back.

Zillgitt said that, for certain types of epilepsy, “the meds just aren’t going to work.”

“There’s pretty consistent numbers, which is somewhat sobering — about 1 in 3 people with epilepsy do not become seizure-free with meds, so 2 out of 3 do, which is good,” Zillgitt said. “But that’s not enough. … Drug resistance is very common.”

Zillgitt expanded on his thoughts about medication.

“If you start on medication, you have one to two years to see if these meds are gonna work,” he said. “During that time, you’ve probably tried two medications. If you’ve tried two medications and you’re still having seizures, then epilepsy surgery may be a better course of action for you.”

Zillgitt said that some people don’t have a warning sign prior to having a seizure, but that an overwhelming sense of fear and anxiety, seeing flashing colored lights, and having a “terrible” smell or a “terrible” taste in the mouth could be symptoms of epilepsy.

In such cases, he suggests people let their primary care doctor know so that they can potentially be referred to a neurologist.

According to the release, epilepsy affects approximately 3.5 million people in the United States.

Peter Varga shared a message for individuals who may be experiencing seizures.

“They’re going to do tests, I understand that, but after a year of doing analysis and putting you on different medications, that’s enough — don’t put it into a decade of doing that,” he said. “If you’re having grand mal seizures so often, please go and have what I had done. … Go and see a doctor.”

Publication select ▼

Publication select ▼