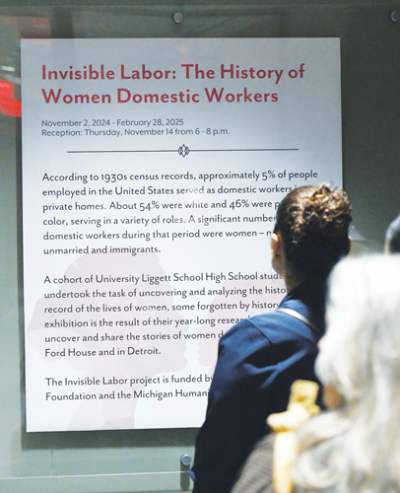

“Invisible Labor,” an exhibition about 20th century domestic workers in the Grosse Pointes and Detroit, is on display now at the Edsel and Eleanor Ford House Visitor Center.

Photo provided by University Liggett School

GROSSE POINTE SHORES — They were the people — mostly women — who spent their lives cooking, cleaning and caring for the children of the elite, but their stories have largely been forgotten. Until now, that is.

“Invisible Labor: The History and Impact of Domestic Workers in Grosse Pointe and Detroit,” on display through Feb. 25 in the Edsel and Eleanor Ford House Visitor Center in Grosse Pointe Shores, is an exhibition researched and prepared by University Liggett School students that documents the lives and contributions of these workers in the 20th century. Under the direction of ULS librarian and teacher Karen Villegas, director of information services and global online learning, and Ford House Director of Material Culture Lisa Worley, students spent a year researching, collecting materials and preparing the exhibition.

“The stories of these women have remained largely untold,” Worley said in a press release. “This project not only brings their contributions to light but also empowers students to engage deeply with history.”

Because almost all these workers lived before the advent of social media — and, in many cases, before the internet — students didn’t have the benefit of a digital footprint to follow as they would with modern figures.

“These people were essentially invisible, and finding information on them was kind of an impossible task,” Villegas said. “These kids followed the path wherever it led.”

Still, there were ways they could find information, even if it meant more extensive digging than a Google search.

Students did some of their research using the online tool Ancestry Classroom. Senior Elizabeth Dickey, of Grosse Pointe Woods, looked into the life of Ada Alice Hill and discovered Hill’s immigration papers, marriage license and declaration of intent that she wanted to become a United States citizen.

“What definitely surprised me was how much I could find on my person,” Dickey said.

Thanks to grants from the Edward E. Ford Foundation, Americana Foundation and the Michigan Humanities Council, Villegas said the students were able to expand their research to include not only staff who had worked at the Ford House, but also other workers in the area, most notably Mary Upshaw McClendon, a trailblazer in the fight for the rights of domestic workers. McClendon, who began cleaning homes at age 9 in her native Alabama alongside her mother, moved with her family to Detroit in 1955. Despite having limited resources, she formed the Household Workers Organization in 1969 to get better pay and conditions for domestic workers. At 54, she attended community college to become a certified home care aid. She was born in 1922 and died in 2015. Her papers are among the archives at the Walter P. Reuther Library on the Wayne State University campus in Detroit.

A single mother, McClendon ran HWO out of her home. She wrote numerous letters to politicians to advocate for laws to better the lives of domestic workers.

Some of the students, including senior Da’Mya Johnson, of Detroit, spent time combing through McClendon’s papers and other archives at the Reuther.

“At Liggett, we’ve done a lot of place-based research from primary sources,” Villegas said.

Conditions were often harder for domestic workers than they were for other worker groups, because most of those employed in this field were from marginalized groups.

“One of the reasons they didn’t have these rights was because they were immigrants or Black people,” Johnson said.

Villegas said one of the subjects of the project was a woman from France who served as a governess to the Ford children. While she had a relatively good salary for the time, she never married or had children of her own because her work caring for another family’s children was so demanding. Villegas said the governess would save her money to visit her sister in France every couple of years.

“A lot of these women were divorced or never married. … (They had) limited options” as far as employment to support themselves, Villegas said.

Their jobs also typically entailed difficult manual labor with no health benefits or sick time.

“You are doing really hard work for really low wages,” Villegas said.

That was the case for McClendon, who worked tirelessly for years.

“One of the things I found shocking was even though she fought for so many rights … she died without any benefits at all,” Johnson said of McClendon, who suffered from debilitating chronic back pain in her later years.

The project is generating some recognition for McClendon, a historical figure whose legacy has been largely overlooked. Johnson said the Louisa St. Clair Chapter National Society Daughters of the American Revolution plans to give an award to McClendon’s surviving family members. Although the date for that event hadn’t been set at press time, Johnson is expected to be there and is looking forward to meeting McClendon’s granddaughter.

“For the most part, she lived a really powerful life,” Johnson said.

McClendon was someone who encouraged people to get a good education, as Johnson said McClendon believed it would give them greater opportunities to better themselves. As Villegas pointed out, most of the workers never owned their own homes, whether because they were living in the homes of the people for whom they worked or because they couldn’t afford one.

Besides learning how to use online and archival research to find information about ordinary people, students were introduced to the process of creating panels for a museum exhibition, where they had to consider everything from font size to photo placement to the amount of text a visitor would read.

The exhibition comes at a time when Ford House officials have been re-creating the historical home’s domestic quarters to give visitors a glimpse into the lives of the staff who worked there.

“They didn’t have a lot of information on the (staff),” Villegas said. “We thought that it would be a cool way to engage the kids in history and the research process.”

Senior Isabel Jenkins, of Harper Woods, said she appreciated that this was a local history project, which she said made it easier to connect with on a personal level. She also found the research eye-opening.

“It definitely did change my perspective on a lot of things,” Jenkins said.

This project was voluntary and students gave up their summer last year to work on it.

“It was worth it,” Johnson said. “I would definitely do it again. Learning about (McClendon) was invaluable.”

Other students who worked on the project include Alexander Gould, Jillian Whitton, Nadia Le, Alexander Macek, Ari Medvinsky, Mya Shah-Littles, Elizabeth Dickey, Kiki Donaldson and Donald Rowlands. All will be graduating this spring.

Medvinsky and Whitton even had a chance to present their research during the American Association for State and Local History national conference in Mobile, Alabama.

“People were clamoring to talk to the kids,” Villegas said of the professional historians in attendance. “They were really interested in their experience.”

There’s no admission charge or reservations needed to view “Invisible Labor.” A Ford House spokesperson said by email that the public can stop in the Visitor Center during operating hours to see it.

The Ford House is located at 1100 Lake Shore Road in Grosse Pointe Shores. For hours of operation and more information, visit fordhouse.org or call (313) 884-4222.

Publication select ▼

Publication select ▼