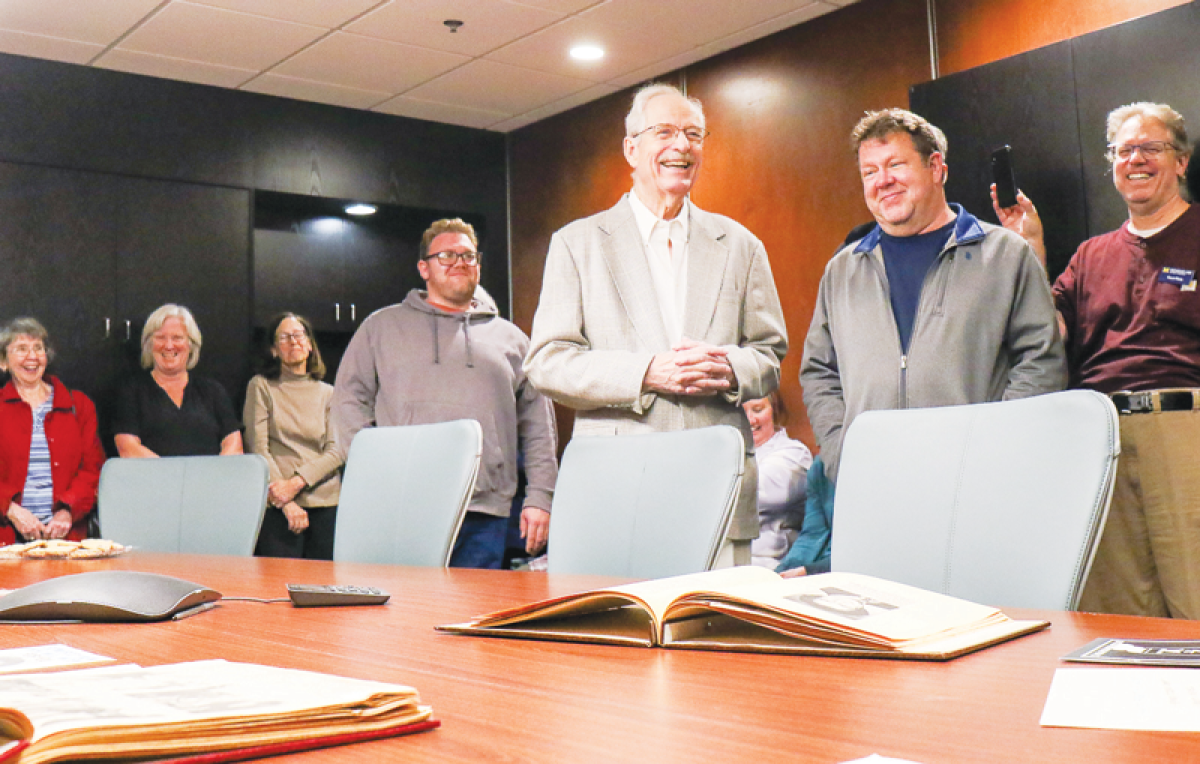

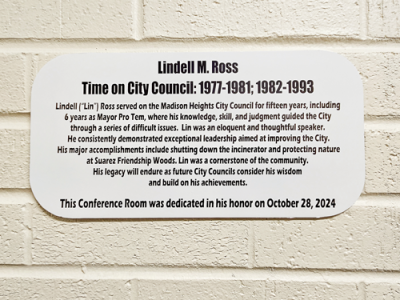

A plaque outside the door to the conference room commemorates the dedication.

Photo by Patricia O’Blenes

MADISON HEIGHTS — Today, Madison Heights residents enjoy cleaner air, safer roads and more green space thanks in part to Lindell “Lin” Ross. The former City Council member helped shut down a trash incinerator, pushed for five lanes on 13 Mile Road instead of four, and rescued Suarez Friendship Woods from development into homes.

Now, his name adorns a plaque outside the executive conference room at Madison Heights City Hall, located at 300 W. 13 Mile Road. The room is where officials study sensitive issues before they vote in the council chambers.

Ross, 85, was there Oct. 28 at a dedication ceremony in his honor. The room was packed to capacity with current council and staff, as well as family, friends and neighbors.

Ross still lives in Madison Heights and served on the council for 15 years: 1977-81 and 1982-93, including six years as mayor pro tem. He resigned in 1993 to run for mayor — a step that is no longer required by the city charter — but lost to George Suarez, the incumbent.

While Ross never returned to politics, supporters say he had already cemented his reputation by that point as a model public servant.

“Lin was ahead of his time,” said Mark Bliss, the current mayor pro tem, after the dedication. “The issues that he tackled, today, would be super popular and common sense … but he was a strong voice of leadership on these issues at a time when they weren’t as prevalent.”

One such issue was the effort to save Suarez Friendship Woods, on 13 Mile Road just west of Dequindre Road. In 1981, the 35-acre tract of land was known as Simonds Woods, and it was at risk of being sold by the Lamphere Schools district for development into homes.

Ross urged the school board to preserve the land as park space, siding with a group known as the Friends of Simonds Woods. While protecting a park may seem like a popular position in 2024, back then it was political poison. Many voters in the district felt the home-building opportunity was too lucrative to pass up. As a result, Ross lost hundreds of supporters, and in turn, the election of 1981.

“They were mad at me (in the Lamphere Schools district). Very mad. And I knew it, and I knew that it would cost me my seat,” Ross said in an interview in the conference room. “But I truly believed the woods were more important than my council seat. It’s very rare in this area to have 35 acres like that.”

Despite the political setback, his call for action endured. When the Lamphere Schools district received a state grant that satisfied its financial needs, it caved to growing public pressure and allowed the city to rezone the property as a nature preserve.

The city manager at the time suggested renaming the park in honor of the mayor, but Ross insisted on also dedicating it to the Friends group that helped save the forest in the first place. It thus became known as Suarez Friendship Woods. Home to the Red Oaks Nature Center, the park is currently managed by Oakland County through a lease with the city.

As for Ross, his time off the City Council was short-lived. He returned within a year, appointed back to the panel when two sitting members vacated their seats: one due to death, and another due to a work transfer out of town.

It was only a matter of time before Ross had another fight on his hands, calling for the closure of the trash-burning incinerator on John R Road north of 12 Mile Road. The facility was run by the Southeastern Oakland County Resource Recovery Authority. The waste giant sought to expand and modernize the facility.

“We had some indication that the cancer rate was higher around that incinerator than would be expected in the area, and also it was right next door to the junior high school with all those kids, exposing them to all that allegedly clean steam,” Ross said. “There was public support for this issue, thankfully. It was more popular at the time than me giving Lamphere a hard time. The newspapers put heat on SOCRRA. It was the leadership at SOCRRA that were resisting — not the cities.”

Madison Heights mobilized an environmental counsel and staff to challenge SOCRRA in court. Ross personally attended SOCRRA meetings on behalf of the city. He also handed out literature such as a booklet that listed 26 reasons why the incinerator should close, each starting with a different letter of the alphabet. The campaign succeeded, and by the end of the 1980s, the twin smokestacks were no longer pumping out pollution.

Earlier in his time on the council, the city manager put forth a proposal to make 13 Mile Road four lanes. In the 1970s, the road was just two lanes. Feeling it would be safer to make it five lanes instead of four, including a dedicated left-turn lane, Ross sided with his political rival on the council, Robert Raskowski, in a rare display of unity when Raskowski went against the proposal, tipping a divided council toward five lanes, which were completed in late 1977.

“I got the mayor’s attention, and he gave me the floor, and … everyone fell out of their chair, because usually I was opposed to 90% of (Raskowski’s) stuff,” Ross said.

In his personal life, Ross and his wife Patricia have six children, 13 grandchildren and 11 great-grandchildren. He has been retired for more than 20 years from a career that included nearly 40 years in marketing and advertising, 15 of which were as vice president at two different companies.

Ross has spent his retirement in Michigan and Florida, as well as in Colorado, where for more than a decade he has been a part-time resident poet and ranch cook at Powderhorn Guest Ranch, run by his daughter in the Rocky Mountains.

His weekly poetry readings around the campfire there were met with such a positive response that he published 100 of them in his book, “The Old West,” each based on a true story about life on the frontier in the 1800s. Ross himself was born on a cotton farm in southeast Missouri, where he would play cowboys and Indians with his friends and collected arrowheads throughout the area.

He also tried his hand at newspaper writing with a weekly volunteer column for more than year in the Madison Heights Reporter, where he chronicled people, places and everyday living in a series called “Slices of Life.”

As for the room at City Hall, the Madison Heights Historical Commission was behind the effort to rename it in honor of Ross. It’s part of a larger ongoing initiative to honor those who have made contributions to the community.

The Historical Commission is chaired by Margene Scott, herself a former council member.

“Ross never did (council service) for the glory. He did it for the betterment of the city,” she said. “When (Ross) left his seat to run for mayor … I got to sit in his seat, since that was the only vacant seat after he left. And when I sat there, I always thought about (Ross). He was a role model for me. He really was. And I never did it from a place of politics. I was there to be a public servant.”

Bliss said that philosophy of service to others should be an example to other aspiring leaders.

“I’m hoping his name coming into this room will inspire future councils to make the same sorts of tough calls as Lin Ross, and to be as forward-thinking as him,” Bliss said.

Ross said he originally ran for office because some council members at the time were violating the city charter by issuing direct orders to staff. He said there was even a time when a couple council members used an on-duty police car to travel to the airport in Detroit for a conference.

“I was outraged at the conduct of some on the council,” Ross said. “I had a good job and a good academic background and a good ego. I didn’t need any of those reasons to run for office. But we had some members who were motivated by those things. I was in a situation where I could ignore all of that, where I could do what was the right thing to do. I don’t know if that came from my southern fundamentalist early background, but I look at things on an ethical and moral basis.”

Ross had some words of advice for those seeking elected office.

“Just start at the bottom and learn what you’re doing so that you do a good job at each level,” Ross said. “It’s about the satisfaction of preventing bad things, and making good things happen.”

Publication select ▼

Publication select ▼