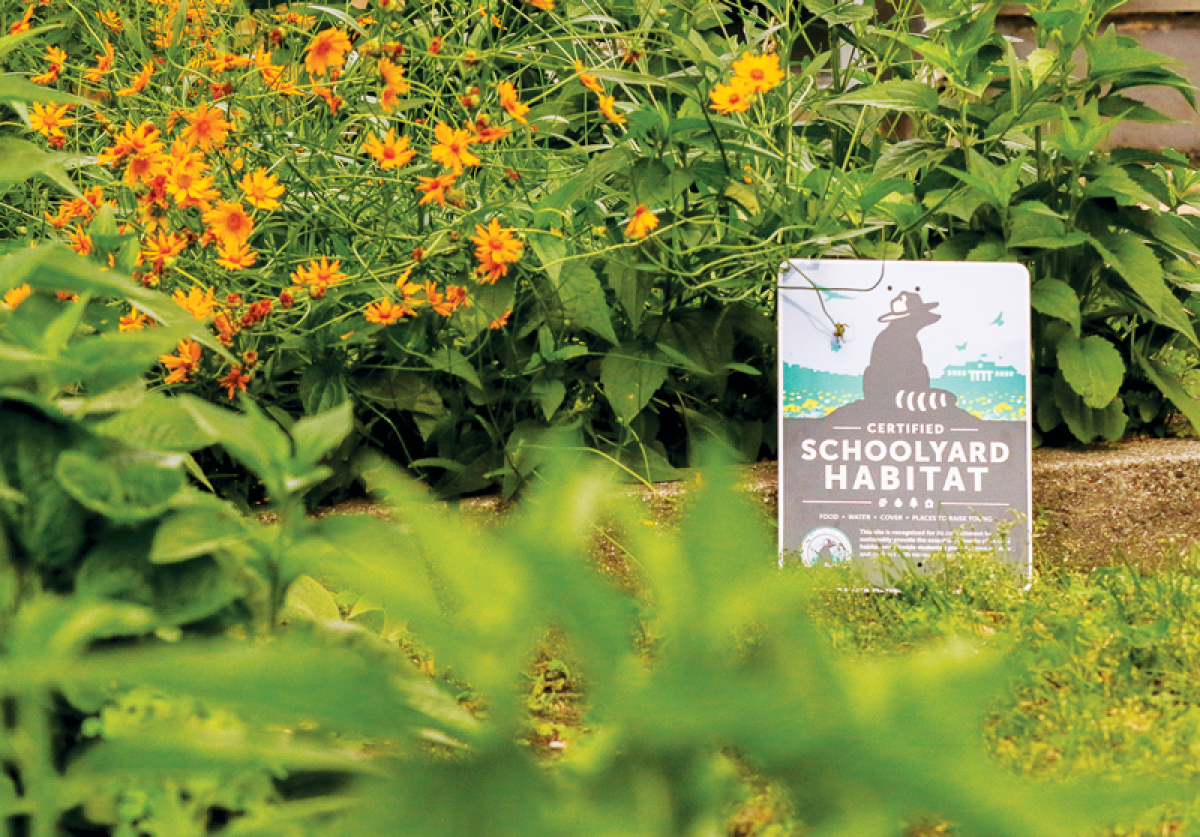

Students in the Ecology Club at John Page Middle School have created a courtyard garden with funds from the Madison Heights Environmental Citizens Committee. The garden features native plants that support pollinators and it was recently recognized by the National Wildlife Federation.

Photo by Patricia O’Blenes

MADISON HEIGHTS — What began as a small gardening club at John Page Middle School in the Lamphere Public Schools district has grown into something more, with one project receiving acclaim from the country’s largest wildlife conservation group.

Rachel Harwell, a science teacher at Page who leads the Ecology Club, said she was approached last winter by school administrators who had been contacted by Nickole Fox, a parent who has a child at Page and serves on the city’s Environmental Citizens Committee.

The ECC was offering grants through its Bloom Project, funding native pollinator gardens in spaces around town — in this case, an interior courtyard at the middle school. Harwell agreed that it would be a great teaching tool for her students.

“I applied for the grant and figured it would be a good way to get the kids involved hands on, digging in the dirt,” she said. “At the time, it wasn’t really related to anything we were doing in class, but I saw it as an opportunity to literally grow something with them, and to really have a connection with the world around them. Today, there is a bit of a disconnect (for students) between what happens in the natural world and on their phones.”

Harwell said the courtyard was well suited for the project, which incorporates native plants such as milkweed, bee balm, coneflowers and asters. These provide food, cover and nesting places for pollinators including butterflies, bees and birds.

“It’s very protected from things like deer and rabbits, and it’s an excellent habitat for birds and flying creepy crawlers who are pollinators. And those pollinators are fantastic for food production. We can’t do anything without them,” Harwell said. “When you replace invasive plants with native, you’re also doing great things like retaining water so you don’t need to water as often, and there’s less flooding. The roots run deep, too, so they do a great job of cleaning the soil.

“So it’s more than just supporting pollinators,” she said. “It gets us thinking about how we can take a lawn that requires so much maintenance and transform it into something beautiful that will maintain itself, and really improve the health of the ecosystem where we live.”

Recently, the school garden received special recognition from the National Wildlife Federation, billed as America’s largest wildlife conservation and education organization. The NWF declared the garden a “Certified Wildlife Habitat” through its Garden for Wildlife movement.

Since 1973, the program has recognized more than 300,000 gardens, spanning an estimated 4 million acres. Some of them are located on school grounds, like the garden at Page, while others can be found in backyards and urban gardens, or at businesses, churches, parks, farms and zoos.

According to the NWF, research shows certified properties have the potential to support twice as much wildlife compared to noncertified properties.

“Anyone, anywhere, can restore wildlife habitat right in their own yards and communities,” said David Mizejewski, an NWF naturalist, in a statement. “Whether you garden in a suburban yard, an urban area or a rural plot of land, you can make a difference for local wildlife.”

As a bonus, the NWF also gives each certified garden its own personalized certificate with a unique habitat number, a one-year membership to NWF that includes a subscription to its magazine and e-newsletter, discounts on the NWF catalog, rights to post a Certified Wildlife Habitat yard sign, and discounts on native plants at gardenforwildlife.com.

As for the Ecology Club at Page, it’s open to anyone at the school, comprising a mix of grades. Members meet after school twice a month on Tuesdays, with extra meetings as necessary.

“Our group started very small, but it is growing. The kids have really taken to it,” Harwell said. “A lot of them come in and say they plant with their grandparents, or their mom has this in the yard. They want to know more about each plant, maybe because they have it at home. But they’ve also been very open-minded, with no pushback wanting certain types of flowers. There is such a thing as overexplaining things, but when they engage with it, they’re doing something and really understand.”

During the winter, when it may be too cold to work in the garden, the group works indoors, doing research for the spring when they can get back outside. They learn about the needs of animals, build items like bird feeders, and discuss what items to add to the garden, and where.

“Going into winter, we didn’t do any grooming in the garden, since with native plants you want to leave them there so the birds can come and eat the seeds, and many pollinator (insects) will lay their eggs and burrow in the stems of dead plants, which becomes a habitat in itself,” Harwell said. “The kids really get to see it work.”

Harwell said the Ecology Club now has even greater ambitions.

“The goal moving forward is to start doing small gardens around the exterior of Page, so that they’re more noticeable to the community,” she said. “Maybe we can be a reference for other people. Like they will look at our garden and say, ’Hey, look at that. That’s easy enough for us to do.’”

Publication select ▼

Publication select ▼