Bigelow served as a lieutenant commander in the U.S. Navy during WWII. Seen here circa 1944-45, he was stationed at a lab in Washington, D.C., and addressed issues with lubrication that affected ships.

Photo provided by Debby Bigelow

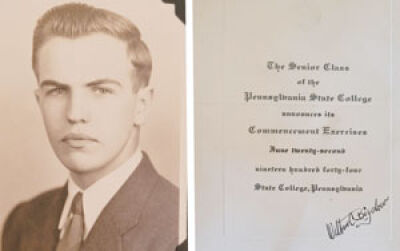

Bigelow graduated from Penn State University in 1944 with a bachelor’s degree in agriculture and biological chemistry.

Photo provided by Debby Bigelow

Bigelow pictured in November 1987 during his tenure at the University of Michigan.

Photo provided by Debby Bigelow

Wilbur Bigelow poses for a photo with, from the left, granddaughters Alena and Natalie Bigelow, daughter-in-law Debby Bigelow, and son Andrew Bigelow.

Photo provided by Sarah Wozniak

NOVI — Scientists from around the world flocked to Ann Arbor March 16 to honor Novi resident Wilbur Bigelow, a professor emeritus at the University of Michigan, with a surprise 100th birthday party.

Bigelow taught at the university for 40 years and then remained active with the university well into his 90s. Many of his former students have gone on to have their own impressive careers. This includes Elizabeth Holm, the department chair of materials science and engineering at U of M.

“I had Professor Bigelow back when I was a student here in the 1980s. So, this is pretty amazing to have a 100th birthday celebration for someone that I had in my class, and he hasn’t changed. I mean he’s gotten older, but the attitude is still the same,” said Holm. “He always told it just like it was, and he still does.”

Bigelow greeted his guests with his characteristic “cranky” yet witty attitude, which his former student Cheryl (Christenson) Dalsin, of Tempe, Arizona, described as his “charm.” When those gathered asked how he was doing, he simply said he was “old and cranky,” and proceeded to shake hands and converse with his guests.

Amy Mercado, of Dayton, Ohio, studied under Bigelow in the late ’80s and early ’90s and said that while he seemingly has a tough exterior, he is very generous and cares deeply for his students. She said that there was a time during her schooling when he not only helped her to obtain a position at a local lab about 5 miles from campus, but he provided her with a means of transportation to get there.

“He was really into his students. He always said he didn’t like any student to fail, so he would do whatever he could so that nobody would fail,” said Mercado. “He helped me because there was an opening in a lab that was probably 5 miles off campus, and I couldn’t figure out how to get there. I was very grateful that he helped me find this job in the laboratory working with the type of electron microscopes that we used in class or in the labs, but I didn’t know how to get there, so I was kind of in a conundrum, and he told me not to worry about it. He said, ‘What I’m going to do is I’m going to put my car keys on my desk every day that you have to go to work and you take my car and you bring it back and you put my keys right here in the same spot.’ And I was extremely grateful for that.”

She went on to say that when he discovered she was putting gas in the car to supplement her usage, he told her to never do that again. Mercado said she was shocked, but he knew that she didn’t have a lot of money at the time and didn’t want her to spend it on gas.

“That’s the kind of person he is. Even though he seemed to have kind of a crusty exterior, he did that kind of thing for his students,” said Mercado.

Life in academia

The surprise party featured an introduction by Holm and presentations by three of his former students who are now well known in the field of materials science: Larry Allard, of Oak Ridge, Tennessee; John Mardinly, of Chandler, Arizona; and John Mansfield, of Ann Arbor.

“I think this is an unprecedented event. I don’t think we have had anyone reach 100 years. A century of contribution, and I do mean contribution. Professor Bigelow has continued to contribute to the department and to science all the way through his life, and we have people here that are still influenced by what he does and did and continues to do,” said Holm.

The men presented highlights and photographs from Bigelow’s career. This included acquiring two up-to-date transmission electron microscopes in 1962 and 1963, and founding the university’s Electron Microbeam Analysis Laboratory in 1969, which he was director of until 1987. Bigelow told the Novi Note during a March 9 interview that he considers this to be the crowning achievement of his scientific career. In 1985, he also established the Hanawalt Laboratory for X-ray Diffraction.

“I would have to say his tenacity and determination (are his greatest strengths). Once Dad takes on a project, he will always find a way to see it through, or figure out a solution to a problem, regardless of how long it may take, or what obstacles may arise along the way,” said Andrew Bigelow, Wilbur’s son. “A good example of this was related by Dr. Allard when he described how he and Dad spent almost two years figuring out how to accurately aim the electron beam on one of their microscopes. This is typical of Dad’s tenacity; he would figure out a way to make that machine work, regardless of how long it took.”

In the beginning

Bigelow was born on March 18, 1923, and grew up in the rural town of Bowman Creek, Pennsylvania, in a house that his father built. He was one of four children. Growing up, he did not have running water and electricity or even a telephone in his home. He said they had to pump water and carry it up to the house.

He recalled having to go to the neighbor’s house to use the telephone, until his father was able to save enough money to have a telephone line put in. However, he said that he was not excited when the telephone was put in, as he couldn’t use it.

“Kids don’t use the telephone,” Bigelow said matter of factly.

He said they had plenty of food, as they raised animals for meat and grew vegetables and fruits in a garden. He said that they weren’t poor during the Great Depression, as they had plenty of food to eat and were able to go to good schools.

“I had a great time as a child,” said Bigelow. “Roamed the hills and swimmed the creeks. It was a great childhood. … We were never poor. We just didn’t have money.”

He recalled listening to the radio at his grandfather’s house. He said the family would gather around the Atwater Kent radio and listen to whatever was on.

“It was all noisy, and we had to run the antenna over a tree and over another tree to get a decent signal, and whatever was on we listened to. I didn’t get a choice. The parents decided what we were going to listen to,” he said.

During that era, Bigelow recalled, his father always brewed beer in the basement. However, he said that was not what inspired him to go into science. He said that he attributed his desire to go into science to an agricultural science teacher he had in high school.

Scientific pursuits

He attended Pennsylvania State University, where he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in agriculture and biological chemistry in 1944. He said his college degree was funded by raising and selling chickens. Bigelow said the family would raise and sell around 200 chickens each year, and the funds paid for his education. He said he spent $525.77 per year for his bachelor’s degree.

“The cost has gone up remarkably over the years, but I graduated before that happened,” said Bigelow.

Upon graduation, he was offered a commission in the United States Naval Research Lab in Washington, D.C., which he gladly accepted. He then worked his way up the ranks by “cheating a little” and taking correspondence courses to finish his military career as a lieutenant commander. He said his military service was focused on solving the Navy’s lubrication and corrosion issues. There he worked with W. A. Zisman, a famous surface chemist.

“I stayed on as long as I could. I liked the Navy uniforms. It was the first time I ever had a suit of clothes that fit me,” Bigelow said. “Because all I got were hand-me-down clothes from my uncles. I got to go into a tailor shop and got fitted for two uniforms, and they fit nicely and they looked good. I hated to get out of the Navy because I had to give up those clothes. … You get to keep it but you can’t wear it.”

He left the military in 1946 and then earned his master’s in chemistry in 1948 and his doctorate from the University of Michigan in physical chemistry in 1952. Bigelow said he chose to come to Michigan because a man he worked with in the Navy was well acquainted with U of M and sent him to the university on a teaching fellowship with Dr. Lawrence Brockway.

“That was a real good thing to do, because Dr. Brockway was a world-famous man and he trained me well in chemistry and everything,” he said. “(I learned) everything (from Brockway); he was more like a father than my father. He was a great man.”

Family life

During his fellowship he met Alyce Carlene Friedley. She was also a fellow in the chemistry program and based her career at U of M teaching chemistry. The two of them married and had two sons, Andrew and Douglas.

“She was a very nice person,” he said of his late wife. She died in 1991 of complications from breast cancer surgery.

Bigelow said his marriage of 40 years taught him to be kind.

“You be sure to never say a harsh word to your mate. If you start to say something nasty, then you stop and count to five and think of something pleasant to say. It is important to be kind,” said Bigelow.

His son, Douglas, had cerebral palsy and was both physically and mentally disabled. Bigelow cared for his son for 58 years until he died in his sleep.

“He was a cheerful little guy, but he was severely handicapped. All he could do was throw things on the floor and laugh when I had to pick them up,” Bigelow said of his son.

Researching and teaching at U of M

After graduating from U of M, Bigelow worked for professor J. W. Freeman as a research associate in the U of M Engineering Research Institute studying the development of precipitate phases at high temperatures in several alloys then in use in jet aircraft engines, using the techniques of electron microscopy and electron diffraction, according to his biographical summary. He remained there until 1955, when he became a faculty member of the university.

Bigelow’s scientific work has involved the application of the methods of electron microscopy and X-ray and electron diffraction to the study of structure-property relationships in engineering materials, according to his biographical summary. He has also collaborated in research on surface chemistry and lubrication; scale formation in the conversion of saline to fresh water; the distribution of silica and heavy metals in plant tissues; and indexing methods for X-ray powder diffraction data, according to his biographical summary. Bigelow identified Gamma Prime Ni3AI with electron microscopy in the 1950s.

Dalsin offered a better explanation of material science for those not familiar with it. She explained that it is like making cookies. You can have the same ingredients, but if you cook it less, it is soft, and if you cook it longer, it comes out crispy. The science focuses on how to make materials better acclimated for different purposes.

Bigelow taught many science courses over the years. He said he taught everything from general chemistry to physical chemistry to physical metallurgy, X-ray diffraction, crystallography, electron microscopy and even a statistics course. He said he was told to teach advanced statistics and had to learn it before that fall semester.

“Ignorance to a subject is no excuse for not teaching it,” said Bigelow. “You just have to study faster than the students.”

Following his retirement from the university in 1993, Bigelow remained active as a consultant.

Vitamins and longevity

“My greatest achievement — living to be 100,” Bigelow declared in a March 9 interview with the Novi Note. He said the secret to living a long life is “Vitamins. All of them. Take a bunch of vitamins. The most important ones are C and D. I took a bunch of vitamins. I took them almost all my life, and this is the result.”

Debby Bigelow, Wilbur Bigelow’s daughter-in-law, recalled that he would carry a list of all the different vitamins with him.

“He actually used to carry a strip in his wallet with what he took because people would be so amazed at his age, and he would keep a piece of paper with what he took every day,” she said. “And he would share that with people to help them stay healthy.”

Bigelow is a charter member and fellow of the Microbeam Analysis Society, and served as president of the Michigan Chapter in 1979. According to Allard, Bigelow is the oldest living member. He was named a Fellow of the Society in 2018.

He has also been a member of the Electron Microscopy Society of America since about 1950, having served as national program chairman in 1960, director from 1961 to 1963, president of the Michigan Chapter in 1965, national membership secretary in 1966 and 1967, and national president in 1969. He was named a Fellow of the Society in 2019. He is a longtime member of the American Chemical Society, and has been a member of the Alpha Chi Sigma, Sigma Xi, and Tau Beta Pi academic honors societies for over 70 years.

Fun stuff, giving back and profound thoughts

Bigelow loves football and is a huge fan of the University of Michigan team. He said he went to all the games from the time he was a student through his time as a faculty member. However, he now watches the games on television. When it comes to professional football, he said he feels obligated to root for the Detroit Lions, but admitted he naps through their games. He also enjoys music and used to like to go to symphony concerts in Ann Arbor, as well as to the theater. According to Debby Bigelow, his favorite symphony is Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5.

Bigelow pointed out that the University of Michigan is only 200 years old and therefore he has been around for a good percentage of its history.

“I don’t have a favorite memory. I have a hundred years of memories, and I sit and go over it all the time,” said Bigelow. He said he thinks about all the people he knew and all the things he didn’t do.

Bigelow enjoys giving back to the community and helping students pursue their educations. Following the death of his wife, Bigelow established the Carlene Friedley Scholarship with a donation of $20,000. The scholarship is handed out annually to a female student pursuing a degree in chemistry. In the 2010-2011 school year, the scholarship was awarded to Sushan Yang, of Novi. He also established the Wilbur C. Bigelow Materials Science and Engineering Scholarship Fund with a $25,000 donation in 2019.

“By doing that he has helped a lot of students continue their programs,” said Debby Bigelow.

Wilbur Bigelow was living on his own until the age of 99 1/2, when an injury following a trip put him at the Novi Lakes Health Campus rehab facility so that he could be near his son, and later his family decided he should remain there for his own safety.

“It’s been a challenge because he is so independent,” said Debby Bigelow.

Andrew Bigelow recalled asking his dad who he thought the greatest president was. He said Wilbur responded “probably FDR.” Andrew said he thought to himself, wow. He’s not just saying that from reading about it. He actually was alive when FDR was president.

“I was like, my gosh, this guy’s talking from personal experience, about the 1930s, the 1940s. I thought that was pretty amazing,” Andrew Bigelow said.

“It’s just an ordinary life,” Wilbur Bigelow told the Novi Note during a March 9 interview, as he didn’t think there was a need to fuss over him. “I’m unremarkable.”

“Ordinary? That’s not ordinary. After hearing all of this, that’s extraordinary,” said Sarah Wozniak, life enrichment director at the Novi Lakes Health Campus, following the remarks from his former students at the party.

“I am surprised, pleased and honored by this meeting,” Bigelow told the crowd. “I did not expect all this hubbub about my 100th birthday, but it is awful nice, and I appreciate all of your thoughts and wishes and the kind things you say about me. Most of them aren’t true. I’m a grumpy old curmudgeon. You can’t beat that. So I thank you all.”

The Novi Lakes Health Campus worked in conjunction with U of M to honor Bigelow with a surprise 100th birthday party. The event was funded as part of the Trilogy Community Foundation’s Live a Dream Program. The program grants wishes for seniors. The party was the wish of his family for him to see his friends, colleagues and the University once more.

Publication select ▼

Publication select ▼